The Confidence Game: What Con Artists Reveal About the Psychology of Trust and Why Even the Most Rational of Us Are Susceptible to Deception

By Maria Popova

“Reality is what we take to be true,” physicist David Bohm observed in a 1977 lecture. “What we take to be true is what we believe… What we believe determines what we take to be true.” That’s why nothing is more reality-warping than the shock of having come to believe something untrue — an experience so disorienting yet so universal that it doesn’t spare even the most intelligent and self-aware of us, for it springs from the most elemental tendencies of human psychology. “The confidence people have in their beliefs is not a measure of the quality of evidence,” Nobel-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman asserted in examining how our minds mislead us, “but of the coherence of the story that the mind has managed to construct.”

The machinery of that construction is what New Yorker columnist and science writer extraordinaire Maria Konnikova explores in The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It … Every Time (public library) — a thrilling psychological detective story investigating how con artists, the supreme masterminds of malevolent reality-manipulation, prey on our propensity for believing what we wish were true and how this illuminates the inner workings of trust and deception in our everyday lives.

“Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours,” Carl Sagan urged in his excellent Baloney Detection Kit — and yet our tendency is to do just that, becoming increasingly attached to what we’ve come to believe because the belief has sprung from our own glorious, brilliant, fool-proof minds. Through a tapestry of riveting real-life con artist profiles interwoven with decades of psychology experiments, Konnikova demonstrates that a con artist simply takes advantage of this hubris by finding the beliefs in which we are most confident — those we’re least likely to question — and enlisting them in advancing his or her agenda.

To be sure, we all perform micro-cons on a daily basis. White lies are the ink of the social contract — the insincere compliment to a friend who needs a confidence boost, the unaddressed email that “somehow went to spam,” the affinity fib that gives you common ground with a stranger at a party even though you aren’t really a “huge Leonard Cohen fan too.”

We even con ourselves. Every act of falling in love requires a necessary self-con — as Adam Phillips has written in his terrific piece on the paradox of romance, “the person you fall in love with really is the man or woman of your dreams”; we dream the lover up, we construct a fantasy of who she is based on the paltry morsels of information seeded by early impressions, we fall for that fantasy and then, as we immerse ourselves in a real relationship with a real person, we must convince ourselves that the reality corresponds to enough of the fantasy to feel satisfying.

But what sets the con artist apart from the mundane white-liar is the nefarious intent and the deliberate deftness with which he or she goes about executing that reality-manipulation.

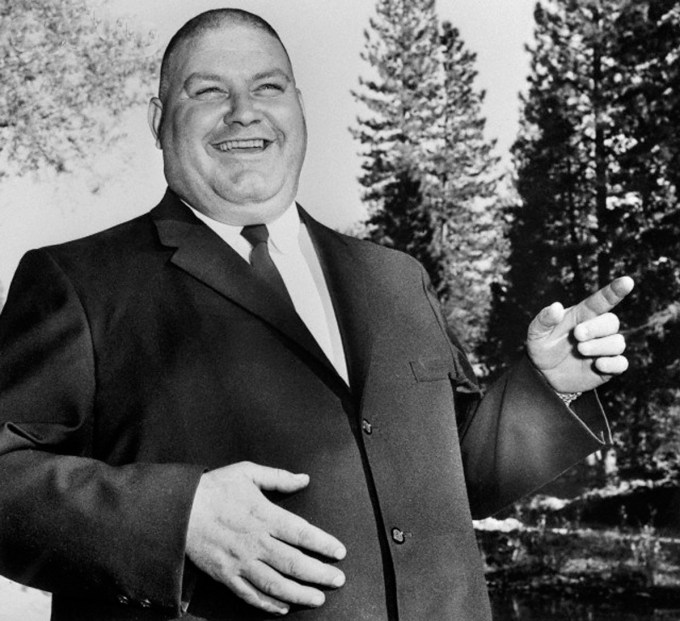

Konnikova begins with the story of a lifelong impostor named Ferdinand Waldo Demara, who successfully passed himself off as a psychologist, a professor, a monk, a surgeon, a prison warden, the founder of a religious college, and even his own biographer.

Considering the perplexity of his astonishing ability to deceive, Konnikova — whose previous book examined the positive counterpart to the con, the psychology of thinking like Sherlock Holmes — writes:

How was he so effective? Was it that he preyed on particularly soft, credulous targets? I’m not sure the Texas prison system, one of the toughest in the United States, could be described as such. Was it that he presented an especially compelling, trustworthy figure? Not likely, at six foot one and over 250 pounds, square linebacker’s jaw framed by small eyes that seemed to sit on the border between amusement and chicanery, an expression that made [his] four-year-old daughter Sarah cry and shrink in fear the first time she ever saw it. Or was it something else, something deeper and more fundamental — something that says more about ourselves and how we see the world?

It’s the oldest story ever told. The story of belief — of the basic, irresistible, universal human need to believe in something that gives life meaning, something that reaffirms our view of ourselves, the world, and our place in it… For our minds are built for stories. We crave them, and, when there aren’t ready ones available, we create them. Stories about our origins. Our purpose. The reasons the world is the way it is. Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty or ambiguity. When something doesn’t make sense, we want to supply the missing link. When we don’t understand what or why or how something happened, we want to find the explanation. A confidence artist is only too happy to comply — and the well-crafted narrative is his absolute forte.

Konnikova describes the basic elements of the con and the psychological susceptibility into which each of them plays:

The confidence game starts with basic human psychology. From the artist’s perspective, it’s a question of identifying the victim (the put-up): who is he, what does he want, and how can I play on that desire to achieve what I want? It requires the creation of empathy and rapport (the play): an emotional foundation must be laid before any scheme is proposed, any game set in motion. Only then does it move to logic and persuasion (the rope): the scheme (the tale), the evidence and the way it will work to your benefit (the convincer), the show of actual profits. And like a fly caught in a spider’s web, the more we struggle, the less able to extricate ourselves we become (the breakdown). By the time things begin to look dicey, we tend to be so invested, emotionally and often physically, that we do most of the persuasion ourselves. We may even choose to up our involvement ourselves, even as things turn south (the send), so that by the time we’re completely fleeced (the touch), we don’t quite know what hit us. The con artist may not even need to convince us to stay quiet (the blow-off and fix); we are more likely than not to do so ourselves. We are, after all, the best deceivers of our own minds. At each step of the game, con artists draw from a seemingly endless toolbox of ways to manipulate our belief. And as we become more committed, with every step we give them more psychological material to work with.

What makes the book especially pleasurable is that Konnikova’s intellectual rigor comes with a side of warm wit. She writes:

“Religion,” Voltaire is said to have remarked, “began when the first scoundrel met the first fool.” It certainly sounds like something he would have said. Voltaire was no fan of the religious establishment. But versions of the exact same words have been attributed to Mark Twain, to Carl Sagan, to Geoffrey Chaucer. It seems so accurate that someone, somewhere, sometime, must certainly have said it.

The invocation of Mark Twain is especially apt — one of America’s first great national celebrities, he was the recipient of some outrageous con attempts. That, in fact, is one of Konnikova’s most disquieting yet strangely assuring points — that although our technologies of deception have changed, the technologies of thought undergirding the art of the con are perennially bound to our basic humanity. She writes:

The con is the oldest game there is. But it’s also one that is remarkably well suited to the modern age. If anything, the whirlwind advance of technology heralds a new golden age of the grift. Cons thrive in times of transition and fast change, when new things are happening and old ways of looking at the world no longer suffice. That’s why they flourished during the gold rush and spread with manic fury in the days of westward expansion. That’s why they thrive during revolutions, wars, and political upheavals. Transition is the confidence game’s great ally, because transition breeds uncertainty. There’s nothing a con artist likes better than exploiting the sense of unease we feel when it appears that the world as we know it is about to change. We may cling cautiously to the past, but we also find ourselves open to things that are new and not quite expected.

[…]

No amount of technological sophistication or growing scientific knowledge or other markers we like to point to as signs of societal progress will — or can — make cons any less likely. The same schemes that were playing out in the big stores of the Wild West are now being run via your in-box; the same demands that were being made over the wire are hitting your cell phone. A text from a family member. A frantic call from the hospital. A Facebook message from a cousin who seems to have been stranded in a foreign country.

[…]

Technology doesn’t make us more worldly or knowledgeable. It doesn’t protect us. It’s just a change of venue for the same old principles of confidence. What are you confident in? The con artist will find those things where your belief is unshakeable and will build on that foundation to subtly change the world around you. But you will be so confident in the starting point that you won’t even notice what’s happened.

In a sense, the con is a more extreme and elaborate version of the principles of persuasion that Blaise Pascal outlined half a millennium ago — it is ultimately an art not of coercion but of complicity. Konnikova writes:

The confidence game — the con — is an exercise in soft skills. Trust, sympathy, persuasion. The true con artist doesn’t force us to do anything; he makes us complicit in our own undoing. He doesn’t steal. We give. He doesn’t have to threaten us. We supply the story ourselves. We believe because we want to, not because anyone made us. And so we offer up whatever they want — money, reputation, trust, fame, legitimacy, support — and we don’t realize what is happening until it is too late. Our need to believe, to embrace things that explain our world, is as pervasive as it is strong. Given the right cues, we’re willing to go along with just about anything and put our confidence in just about anyone.

So what makes you more susceptible to the confidence game? Not necessarily what you might expect:

When it comes to predicting who will fall, personality generalities tend to go out the window. Instead, one of the factors that emerges is circumstance: it’s not who you are, but where you happen to be at this particular moment in your life.

People whose willpower and emotional resilience resources are strained — the lonely, the financially downtrodden, those dealing with the trauma of divorce, injury, or job loss, those undergoing major life changes — are particularly vulnerable. But these, Konnikova reminds us, are states rather than character qualities, circumstances that might and likely will befall each one of us at different points in life for reasons largely outside our control. (One is reminded of philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s excellent work on agency and victimhood: “The victim shows us something about our own lives: we see that we too are vulnerable to misfortune, that we are not any different from the people whose fate we are watching…”) Konnikova writes:

The more you look, the more you realize that, even with certain markers, like life changes, and certain tendencies in tow, a reliably stable overarching victim profile is simply not there. Marks vary as much as, and perhaps even more than, the grifters who fool them.

Therein lies the book’s most sobering point — Konnikova demonstrates over and over again, through historical anecdotes and decades of studies, that no one is immune to the art of the con. And yet there is something wonderfully optimistic in this. Konnikova writes:

The simple truth is that most people aren’t out to get you. We are so bad at spotting deception because it’s better for us to be more trusting. Trust, and not adeptness at spotting deception, is the more evolutionarily beneficial path. People are trusting by nature. We have to be. As infants, we need to trust that the big person holding us will take care of our needs and desires until we’re old enough to do it ourselves. And we never quite let go of that expectation.

Trust, it turns out, is advantageous in the grand scheme of things. Konnikova cites a number of studies indicating that people who score higher on generalized trust tend to be healthier physically, more psychoemotionally content, likelier to be entrepreneurs, and likelier to volunteer. (The most generous woman I know, who is also a tremendously successful self-made entrepreneur, once reflected: “I’ve never once regretted being generous, I’ve only ever regretted holding back generosity.”) But the greater risk-tolerance necessary for reaping greater rewards also comes with the inevitable downside of greater potential for exploitation — the most trusting among us are also the perfect marks for the player of the confidence game.

But the paradox of trust, Konnikova argues, is only part of our susceptibility to being conned. Another major factor is our sheer human solipsism. She explains:

We are our own prototype of being, of motivation, of behavior. People, however, are far from being a homogeneous mass. And so, when we depart from our own perspective, as we inevitably must, we often make errors, sometimes significant ones. [Psychologists call this] “egocentric anchoring”: we are our own point of departure. We assume that others know what we know, believe what we believe, and like what we like.

She cites an extensive study, the results of which were published in a paper cleverly titled “How to Seem Telepathic.” (One ought to appreciate the scientists’ wry sarcasm in poking fun at our clickbait culture.) Konnikova writes:

Many of our errors, the researchers found, stem from a basic mismatch between how we analyze ourselves and how we analyze others. When it comes to ourselves, we employ a fine-grained, highly contextualized level of detail. When we think about others, however, we operate at a much higher, more generalized and abstract level. For instance, when answering the same question about ourselves or others — how attractive are you? — we use very different cues. For our own appearance, we think about how our hair is looking that morning, whether we got enough sleep, how well that shirt matches our complexion. For that of others, we form a surface judgment based on overall gist. So, there are two mismatches: we aren’t quite sure how others are seeing us, and we are incorrectly judging how they see themselves.

The skilled con artist, Konnikova points out, mediates for this mismatch by making an active effort to discern which cues the other person is using to form judgments and which don’t register at all. The result is a practical, non-paranormal exercise in mind-reading, which creates an illusion of greater affinity, which in turn becomes the foundation of greater trust — we tend to trust those similar to us more than the dissimilar, for we intuit that the habits and preferences we have in common stem from shared values.

And yet, once again, we are reminded that the tricks of the con artist’s exploitive game are different only by degree rather than kind from the everyday micro-deceptions of which our social fabric is woven. Konnikova writes:

Both similarity and familiarity can be faked, as the con artist can easily tell you — and the more you can fake it, the more real information will be forthcoming. Similarity is easy enough. When we like someone or feel an affinity for them, we tend to mimic their behavior, facial expressions, and gestures, a phenomenon known as the chameleon effect. But the effect works the other way, too. If we mimic someone else, they will feel closer and more similar to us; we can fake the natural liking process quite well. We perpetuate minor cons every day, often without realizing it, and sometimes knowing what we do all too well, when we mirror back someone’s words or interests, feign a shared affinity for a sports team or a mutual hatred of a brand. The signs that usually serve us reliably can easily be massaged, especially in the short term — all a good con artist needs.

In the remainder of the thoroughly fascinating The Confidence Game, Konnikova goes on to explore the role of storytelling in reality-manipulation, what various psychological models reveal about the art of persuasion, and how the two dramatically different systems that govern our perception of reality — emotion and the intellect — conspire in the machinery of trust. Complement it with Adrienne Rich on lying and what “truth” really means, David deSteno on the psychology of trust in work and love, and Alice Walker on what her father taught her about the love-expanding capacity of truth-telling.

—

Published January 12, 2016

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/01/12/the-confidence-game-maria-konnikova/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr