The Glass Universe: How Harvard’s Unsung Women Astronomers Revolutionized Our Understanding of the Cosmos Decades Before Women Could Vote

By Maria Popova

“No woman should say, ‘I am but a woman!’ But a woman! What more can you ask to be?” trailblazer Maria Mitchell admonished the first class of female astronomers at Vassar in 1876. Mitchell — the first professional woman astronomer in America, the first woman admitted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the first woman hired by the United States federal government for a “specialized nondomestic skill” in her capacity as “computer of Venus,” a one-woman GPS guiding sailors around the globe — paved the way for women in American science through personal example and dedicated mentorship. She marked an event horizon in women’s plight for equality in scientific vocation and intellectual life.

Just as Mitchell’s long life was coming to an end, a new wellspring of opportunity for women astronomers was coming to life at one of the world’s most venerated academic institutions. At the Harvard Observatory, a devoted team of female amateur astronomers — “amateur” being a reflection not of their skill but of the dearth of academic accreditation available to women at the time — was coming together around an unprecedented quest to catalog the cosmos by classifying the stars and their spectra.

Decades before they were allowed to vote and a century before NASA’s unheralded women mathematicians helped put the first man on the moon, these women, who came to be known as the “Harvard computers,” illuminated the composition of stars and classified hundreds of thousands of stars according to a system they invented, which astronomers continue to use today. Their calculations became the basis for the discovery that the universe is expanding. Their spirit of selfless pursuit of truth and knowledge stands as a timeless testament to pioneering physicist Lise Meitner’s definition of the true scientist.

Science historian Dava Sobel, author of Galileo’s Daughter, chronicles their unsung story and lasting legacy in The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (public library).

Sobel, who takes on the role of rigorous reporter and storyteller bent on preserving the unvarnished historical integrity of the story, paints the backdrop:

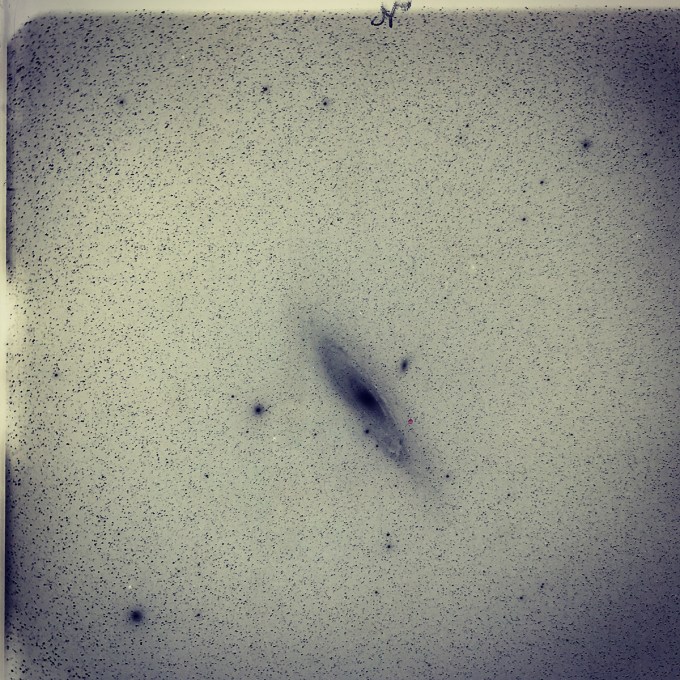

A little piece of heaven. That was one way to look at the sheet of glass propped up in front of her. It measured about the same dimensions as a picture frame, eight inches by ten, and no thicker than a windowpane. It was coated on one side with a fine layer of photographic emulsion, which now held several thousand stars fixed in place, like tiny insects trapped in amber. One of the men had stood outside all night, guiding the telescope to capture this image, along with another dozen in the pile of glass plates that awaited her when she reached the observatory at 9 a.m. Warm and dry indoors in her long woolen dress, she threaded her way among the stars. She ascertained their positions on the dome of the sky, gauged their relative brightness, studied their light for changes over time, extracted clues to their chemical content, and occasionally made a discovery that got touted in the press. Seated all around her, another twenty women did the same.

Among the “Harvard computers” were Antonia Maury, who had graduated from Maria Mitchell’s program at Vassar; Annie Jump Cannon, who catalogued more than 20,000 variable stars in a short period after joining the observatory; Henrietta Swan Leavitt, a Radcliffe alumna whose discoveries later became the basis for Hubble’s Law demonstrating the expansion of the universe and whose work was so valued that she was paid 30 cents an hour, five cents over the standard salary of the computers; and Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin, who became the first person to earn a Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard-Radcliffe.

Helming the team was Williamina Fleming — a Scotswoman whom Edward Charles Pickering, the thirty-something director of the observatory, first hired as a second maid at his residency in 1879 before recognizing her mathematical talents and assigning her the role of part-time computer. Having emigrated to America in a “delicate condition” after the collapse of her marriage, Fleming had to return to Scotland shortly after she joined the Harvard Observatory to give birth to her son, whom she named Edward Charles Pickering Fleming and who would go on to become an MIT-educated engineer. But she returned to Harvard in 1881 and forever changed the gender landscape of astronomy.

Long before Nikola Tesla proclaimed that technology would unleash women’s true potential, Pickering saw an opportunity to involve smart, skilled women in making use of new astrophotography technology and championed that vision fiercely. Ironically, society’s blatant sexism was applied even to his largehearted feminism — the Harvard computers were disparagingly referred to as “Pickering’s harem” for decades. And yet, galling moniker notwithstanding, Pickering’s practice of hiring women became a countercultural act of courage to which we owe a great deal today.

Sobel conveys his rationale:

While it would be unseemly, Pickering conceded, to subject a lady to the fatigue, not to mention the cold in winter, of telescope observing, women with a knack for figures could be accommodated in the computing room, where they did credit to the profession.

Pickering was a visionary man in many regards. Before coming to Harvard, he had revolutionized academia at the newly founded MIT by initiating a sort of proto-hackerspace — a hands-on laboratory where students could cultivate critical thinking by trying on and trying out ideas. He was also an early champion of open-source and refused to patent any of his inventions under the conviction that ideas should be shared freely in order for scientists to build on each other’s work.

Pickering first began hiring women after he ran out of funding and was unable to afford any more paid staff. Shortly after the first class of female astronomers had graduated from Maria Mitchell’s Vassar program, Pickering printed and distributed a plea for volunteers that read like the polar opposite of Shackleton’s recruitment ad. Sobel writes:

He believed women could conduct the work as well as men: “Many ladies are interested in astronomy and own telescopes, but with two or three noteworthy exceptions their contributions to the science have been almost nothing. Many of them have the time and inclination for such work, and especially among the graduates of women’s colleges are many who have had abundant training to make excellent observers. As the work may be done at home, even from an open window, provided the room has the temperature of the outer air, there seems to be no reason why they would not thus make an advantageous use of their skill.”

Pickering felt, furthermore, that participating in astronomical research would improve women’s social standing and justify the current proliferation of women’s colleges: “The criticism is often made by the opponents of the higher education of women that, while they are capable of following others as far as men can, they originate almost nothing, so that human knowledge is not advanced by their work. This reproach would be well answered could we point to a long series of such observations as are detailed below, made by women observers.”

But what ultimately enabled Pickering to hire women as paid observers was the generous patronage of another woman — Anna Draper, the widow of an astrophotography pioneer and herself an ardent proponent of astronomy. Determined to memorialize her husband’s legacy and advance further research through astrophotography, which revealed stars invisible through even the most advanced telescopes, she gave Pickering a check for $1,000 on February 20, 1886, equivalent to more than $25,000 today — the first of numerous installments.

With Anna Draper’s funding, the women of the Harvard Observatory amassed an enormous library of half a million glass plates — Sobel’s “glass universe” — cataloging more stars than anyone had previously thought possible. (Lest we forget, the first comprehensive star catalog had been completed two centuries earlier by another woman, effectively the first female astronomer of the Western world.)

For her part, Williamina Fleming had a much more specific lens on equality. Sobel writes:

Though Mrs. Fleming fully affirmed the principle of equality, she was not an American citizen, and the feminist struggle for the right to vote was not her fight. The cause she championed was equality for women in astronomy. “While we cannot maintain that in everything a woman is man’s equal,” Mrs. Fleming averred in her [National American Woman Suffrage Association presentation], “yet in many things her patience, perseverance and method make her his superior. Therefore let us hope that in astronomy, which now affords a large field for woman’s work and skill, she may, as has been the case in several other sciences, at least prove herself his equal.

(A generation earlier, Maria Mitchell had made a parallel case for why women make better astronomers than men.)

Sobel transports us to the Harvard Observatory to experience the painstaking nature of the work through which the computers arrived at their cosmic revelations:

Mrs. Fleming removed each glass plate from its kraft paper sleeve without getting a single fingerprint on either of the the eight-by-ten-inch surfaces. The trick was to hold the fragile packet by its side edges between her palms, set the bottom — open — end of the envelope on the lip of the specially designed stand, and then ease the paper up and off without letting go of the plate, as though undressing a baby. Making sure the emulsion side faced her, she released her grip and let the glass settle into place. The wooden stand held the plate in a picture frame, tilted at forty-five-degree angle. A mirror affixed to the flat base caught daylight from the computing room’s big windows and directed illumination up through the glass. Mrs. Fleming leaned in with her loupe for a privileged view of the stellar universe. She had often heard the director say, “A magnifying glass will show more in the photograph than a powerful telescope will show in the sky.”

By 1890, Fleming had singlehandedly classified the spectra of ten thousand stars and published the findings in the tome The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, all four hundred pages of which she herself had meticulously proofread. On May 11, 1906 — just four days before her forty-ninth birthday — she received “perhaps the most pleasant shock of her life,” as Sobel aptly puts it: Fleming was elected honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society — an institution far ahead of its time in recognizing women’s scientific work. (Nearly eight decades earlier, pioneering astronomer Caroline Herschel has become the first woman awarded their prestigious Gold Medal.) Fleming became the first American-based woman to earn the distinction.

But, back at the Harvard Observatory, further studies required better technology. Pickering determined that the ideal telescope would be a lavish 24 inches in diameter. (For comparison, Maria Mitchell made her trailblazing comet discovery with a two-inch telescope.) He estimated it would cost a towering $50,000 to build. When Pickering issued a plea for funding, another woman stepped up as the benefactress who would make it possible — Catherine Wolfe Bruce, an elderly painter and patron of the arts who admired science with an outsider’s curiosity.

Sobel surmises:

Perhaps Pickering’s reference to the 24-inch object glass as a “portrait” lens appealed to Miss Bruce’s artistic sensibility. Surely his optimistic enthusiasm provided an antidote to the disquieting article she had recently read by astronomer Simon Newcomb, director of the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office and professor at the Johns Hopkins University. Professor Newcomb predicted that no exciting astronomical finds would turn up in the near or even the distant future. Since “one comet is so much like another,” he asserted “that the work which really occupies the attention of the astronomer is less the discovery of new things than the elaboration of those already known, and the entire systematization of our knowledge.”

As an artist, Bruce must have been particularly put off by such poverty of imagination — the artist necessarily comes at life from the very opposite perspective, which Georgia O’Keeffe memorably articulated: “Making your unknown known is the important thing — and keeping the unknown always beyond you…” Maria Mitchell expressed the same sentiment from the standpoint of science: “The world of learning is so broad… We reach forth and strain every nerve, but we seize only a bit of the curtain that hides the infinite from us.” Bruce surely saw the common ground between art and science in this unflinching insistence that there are always more unknowns to be made known, so she promptly gave Pickering all of the $50,000 needed for the new telescope.

Here, it is worth noting that the story of the “Harvard computers” also raises subtler questions about the cultural narratives woven into our language itself. Why, for instance, do we use the masculine “patronage” when so many of history’s great “patrons” have been women? Anna Draper and Catherine Wolfe Bruce belong to a vast constellation of “matronage” — there are, perhaps most famously, the women of the Medici family, one of whom was instrumental in Galileo’s life; there is Gertrude Stein, who helped the stars of creative visionaries like Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald rise; there is Nadezhda von Meck, without whom there would be no Tchaikovsky. That Draper and Bruce’s generosity continues to sustain the Harvard Observatory more than a century later only amplifies the magnitude of their unheralded magnanimity.

Sobel writes:

[Miss Bruce] volunteered to lend further assistance, not just to Harvard, but to astronomers everywhere, if Pickering would agree to help her choose the most deserving cases. With her promise of $6,000 to start, he announced a call for aid applications in July 1890. He also sent letters to individual researchers at observatories all over the world, asking whether they could put $500 to immediate good use — say, to hire an assistant, repair an instrument, or publish a backlog of data. Nearly one hundred responses met the October deadline. Pickering evaluated the proposals and Miss Bruce approved his recommendation in time for a November selection of the winners. Simon Newcomb, author of the article that had aroused Miss Bruce’s indignation, became one of the first five scientists in the United States to receive her support. Another ten awards went overseas to astronomers working in England, Norway, Russia, India, and Africa.

A century before Primo Levi’s beautiful case for how studying the universe brings humanity closer together, Pickering captured the unifying power of astronomy in his introduction to the list of awardees, published in the Scientific American Supplement that autumn:

The same sky overarches us all.

In the remainder of The Glass Universe, Sobel goes on to chronicle and celebrate the legacy of these extraordinary women, who opened up astronomy and cosmology for visionary scientists like Vera Rubin and Janna Levin. Complement it with the story of the black women mathematicians of NASA and this illustrated homage to women in science, then revisit the story of how astronomer Jocelyn Bell earned the exclamation “Miss Bell, you have made the greatest astronomical discovery of the twentieth century.”

—

Published December 6, 2016

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/12/06/the-glass-universe-dava-sobel/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr