Bertolt: An Uncommonly Tender Illustrated Story about Love, Loss, the Life-Saving Power of Trees, and Learning How to Savor Unlonely Solitude

By Maria Popova

Since long before researchers began to illuminate the astonishing science of what trees feel and how they communicate, the human imagination has communed with the arboreal world and found in it a boundless universe of kinship. A seventeenth-century gardener wrote of how trees “speak to the mind, and tell us many things, and teach us many good lessons.” Hermann Hesse called them “the most penetrating of preachers.” They continue to furnish our lushest metaphors for life and death.

Since long before researchers began to illuminate the astonishing science of what trees feel and how they communicate, the human imagination has communed with the arboreal world and found in it a boundless universe of kinship. A seventeenth-century gardener wrote of how trees “speak to the mind, and tell us many things, and teach us many good lessons.” Hermann Hesse called them “the most penetrating of preachers.” They continue to furnish our lushest metaphors for life and death.

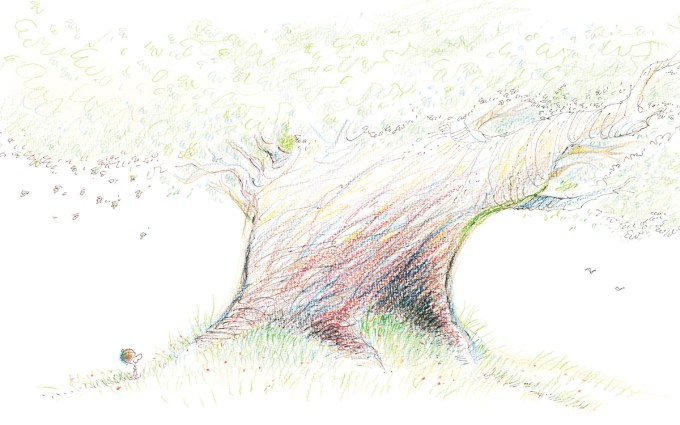

Crowning the canon of arboreal allegories is Bertolt (public library) by French-Canadian geologist-turned-artist Jacques Goldstyn — the uncommonly tender story of an ancient tree named Bertolt and the boy who named and loved it. From Goldstyn’s simple words and the free, alive, infinitely expressive line of his illustrations radiates a profound parable of belonging, reconciling love and loss, and savoring solitude without suffering loneliness.

The story, told in the little boy’s voice, begins with the seeming mundanity of a lost mitten, out of which springs everything that is strange and wonderful about the young protagonist.

He heads to the Lost and Found and walks away with two gloriously mismatched mittens, which give him immense joy but spur the derision of the other boys.

“Sometimes people don’t like what’s different,” he observes with the precocious sagacity of one who knows that other people’s judgements are about them and not about the judged, echoing Bob Dylan’s assertion that “people have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms them.”

But the little boy is unperturbed — a self-described “loner,” he seems rather centered in his difference and enjoys his solitude.

Unlike the other townspeople, who are constantly doing things together, he is content in his own company — a perfect embodiment of the great film director Andrei Tarkovsky’s advice to the young.

Most of all, the boy cherishes his time with Bertolt — the ancient oak he loves to climb.

After seeing a smaller nearby tree cut down and counting its rings, he estimates that Bertolt is at least 500 years old, inching toward the world’s oldest living trees.

From Bertolt’s branches, which he knows with the intimacy of an old friend, the boy observes the town’s secret life — the lawyer’s daughter kissing the motorcycle bad-boy, the Tucker twins stealing bottles from the grocer and selling them back to him, Cynthia the sheep feasting on a farmer’s corn.

There above and away from the human world, he befriends the animals who have also made a home in Bertolt.

He especially cherishes taking shelter in Bertolt during spring storms. He nestles into Bertolt’s branches, which “sway and creak like the masts of a big ship,” and marvels at how the wind presses flattens the reeds against the ground.

In winter, as he rolls his solitary snowball up the hill, the boy dreams of spring and its promise of kissing Bertolt’s barren branches back to lush life. He relishes the first signs of the season and exults when the trees begin to bloom.

And bloom they do — the lime, the elm, the cherry, the weeping willow.

All except Bertolt.

The boy waits for days, then weeks, his hope vanishing with the passage of time, until one day, with the same precocious sagacity, he accepts that Bertolt is dead.

There is great subtlety in this confrontation with death — a death utterly sorrowful, for the boy is losing his best friend, and yet devoid of the drama of the human world, almost invisible.

He observes that while it is unambiguous when a pet has died, a tree “stands there like a huge boney creature that’s sleeping or playing tricks on us.” If Bertolt had been struck by lightning or chopped off, the boy would have understood. But that a loss so profound can be so undramatic, so uneventful, seems barely comprehensible.

It is this penetrating aspect of the book that places it among the greatest children’s books about processing the subtleties of loss.

Since a burial is impossible, the boy, longing to commemorate Bertolt in some way, eventually dreams up a plan in that combinatorial way in which we fuse our existing experiences into new ideas.

We see him running out of the Lost and Found with a box of colorful mismatched mittens, loading them onto his bike, and racing up the hill toward Bertolt.

With steadfast determination, he climbs the giant trunk, the vibrant load strapped to his back, and begins methodically clipping the mittens to Bertolt’s barren branches with clothespins.

In the final scene, amid the respectful silence of Goldstyn’s unworded illustrations, we see Bertolt half-abloom with mittens. Like Christmas ornaments, like Tibetan prayer flags, they stand as an imaginative replacement for the leaves and blossoms that Bertolt’s fatal final spring failed to bring — not artificial, but realer than anything, for they are made of love.

The almost unbearably wonderful Bertolt comes from Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion Books, publisher of such intelligent and imaginative gems as Cry, Heart, But Never Break, The Lion and the Bird, and This Is a Poem That Heals Fish. Complement it with the Japanese pop-up masterpiece Little Tree — a very different yet kindred-spirited arboreal parable about the cycle of life.

—

Published May 12, 2017

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/05/12/bertolt-jacques-goldstyn/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr