Albert Einstein on the Interconnectedness of Our Fates and Our Mightiest Counterforce Against Injustice

By Maria Popova

“We must mend what has been torn apart, make justice imaginable again in a world so obviously unjust, give happiness a meaning once more,” Albert Camus wrote in reflecting on strength of character in turbulent times as WWII’s maelstrom of deadly injustice engulfed Europe. But that mending is patient, steadfast, often unglamorous work — it is the work of choosing kindness over fear, again and again, in the smallest of everyday ways, those tiny triumphs of the human spirit which converge in the current of courage that is the only force by which this world has ever changed.

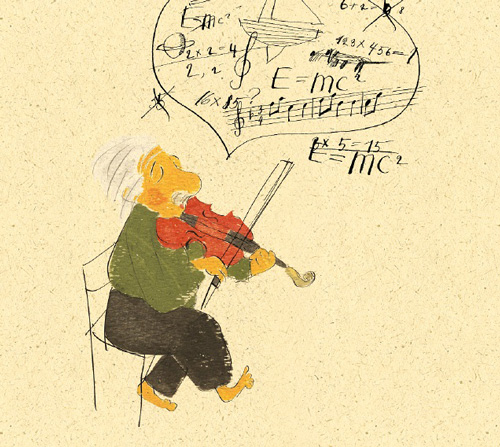

That’s what Albert Einstein (March 14, 1879–April 18, 1955) examined in a beautiful autobiographical piece titled “The World as I See It,” originally published in a 1930 issue of the magazine Forum and Century, and later included in Ideas and Opinions (public library) — the invaluable compendium that gave us Einstein’s reflections on the secret to his thought process, the common language of science, and his increasingly timely message to posterity.

Three centuries after Newton popularized his famous “standing on the shoulders of giants” metaphor, Einstein writes:

How strange is the lot of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose he knows not, though he sometimes thinks he senses it. But without deeper reflection one knows from daily life that one exists for other people — first of all for those upon whose smiles and well-being our own happiness is wholly dependent, and then for the many, unknown to us, to whose destinies we are bound by the ties of sympathy. A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life are based on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received and am still receiving. I am strongly drawn to a frugal life and am often oppressively aware that I am engrossing an undue amount of the labor of my fellow-men. I regard class distinctions as unjustified and, in the last resort, based on force. I also believe that a simple and unassuming life is good for everybody, physically and mentally.

Reflecting on the irreplicable subjectivity of the notion of “the meaning of life,” Einstein considers his own:

To inquire after the meaning or object of one’s own existence or that of all creatures has always seemed to me absurd from an objective point of view. And yet everybody has certain ideals which determine the direction of his endeavors and his judgments. In this sense I have never looked upon ease and happiness as ends in themselves — this ethical basis I call the ideal of a pigsty. The ideals which have lighted my way, and time after time have given me new courage to face life cheerfully, have been Kindness, Beauty, and Truth. Without the sense of kinship with men of like mind, without the occupation with the objective world, the eternally unattainable in the field of art and scientific endeavors, life would have seemed to me empty.

This notion of human fellowship and kinship wasn’t a mere ideological abstraction for Einstein, who lived through two World Wars and witnessed humanity at its worst, yet remained animated by a fundamental faith in the nobility of the human spirit — or, rather, its potential for nobility. He devoted much of his life to “widening our circles of compassion” and advocating for the conditions that nurture this nobility, from his correspondence with W.E.B. Du Bois about racial justice to his encouragement of women to pursue science to his letters to Gandhi about peace and the antidote to violence.

In a passage of chilling prescience, written just before the Nazis unleashed upon humanity our darkest hour, and one of equally chilling pertinence to our own age of rampant propaganda, fear-mongering, and “alternative facts,” Einstein writes:

In politics not only are leaders lacking, but the independence of spirit and the sense of justice of the citizen have to a great extent declined. The democratic, parliamentarian regime, which is based on such independence, has in many places been shaken; dictatorships have sprung up and are tolerated, because men’s sense of the dignity and the rights of the individual is no longer strong enough. In two weeks the sheeplike masses of any country can be worked up by the newspapers into such a state of excited fury that men are prepared to put on uniforms and kill and be killed, for the sake of the sordid ends of a few interested parties.

A year before his death, Einstein revisits the subject in a magnificent acceptance speech for a human rights award conferred upon him by the Chicago Decalogue Society, also included in Ideas and Opinions. He begins with a reminder that questions of meaning and moral values are entirely human-made, for the universe — his primary object of inquiry and the lifelong object of his “passion for comprehension” — is impartial and unconcerned with notions of human rights. A decade before John Steinbeck asserted that “all the goodness and the heroisms will rise up again, then be cut down again and rise up,” Einstein writes:

The existence and validity of human rights are not written in the stars. The ideals concerning the conduct of men toward each other and the desirable structure of the community have been conceived and taught by enlightened individuals in the course of history. Those ideals and convictions which resulted from historical experience, from the craving for beauty and harmony, have been readily accepted in theory by man — and at all times, have been trampled upon by the same people under the pressure of their animal instincts. A large part of history is therefore replete with the struggle for those human rights, an eternal struggle in which a final victory can never be won. But to tire in that struggle would mean the ruin of society.

Eight years before Hannah Arendt’s sobering treatise on the banality of evil and our sole antidote to its normalization, and exactly four decades after Ella Wheeler Wilcox proclaimed that “to sin by silence, when we should protest, makes cowards out of men,” Einstein considers a frequently overlooked yet inexcusable and monumentally reprehensible violation of human rights — complicity with evil by keeping silent against injustice. He writes:

In talking about human rights today, we are referring primarily to the following demands: protection of the individual against arbitrary infringement by other individuals or by the government; the right to work and to adequate earnings from work; freedom of discussion and teaching; adequate participation of the individual in the formation of his government. These human rights are nowadays recognized theoretically, although, by abundant use of formalistic, legal maneuvers, they are being violated to a much greater extent than even a generation ago. There is, however, one other human right which is infrequently mentioned but which seems to be destined to become very important: this is the right, or the duty, of the individual to abstain from cooperating in activities which he considers wrong or pernicious.

Six decades before Rebecca Solnit made her poignant case for breaking silence as our mightiest weapon against oppression, Einstein suggests that the power to speak out against injustice need not be reserved for those professionally devoted to human rights work, nor manifested in grand deeds of activism. He reflects on his own simple, steadfast commitment:

In a long life I have devoted all my faculties to reach a somewhat deeper insight into the structure of physical reality. Never have I made any systematic effort to ameliorate the lot of men, to fight injustice and suppression, and to improve the traditional forms of human relations. The only thing I did was this: in long intervals I have expressed an opinion on public issues whenever they appeared to me so bad and unfortunate that silence would have made me feel guilty of complicity.

Complement this particular portion of Einstein’s wholly indispensable Ideas and Opinions with Elie Wiesel’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech on human rights and our shared duty in ending injustice, Audre Lorde on breaking our silences, and physicist Sean Carroll on how we find meaning in an impartial universe, then revisit Einstein on the secret to learning anything, the nature of the human mind, his letter of advice and solidarity to Marie Curie when she was cruelly attacked, and his remarkable letter of consolation to a grief-stricken father who had lost his young son.

—

Published June 8, 2017

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/06/08/albert-einstein-human-rights/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr