Favorite Children’s Books of 2019

By Maria Popova

Great children’s books are really miniature cartographies of meaning, emissaries of the deepest existential wisdom that cut across all lines of division, scuttle past the many walls adulthood has sold us on erecting, and slip in through the backdoor of our consciousness to speak — in the language of children, which is the language of unselfconscious sincerity — the most timeless truths to the truest parts of us.

Here are the loveliest such truthful, timeless treasures I savored this year. (And in this spirit of timelessness, here are their counterparts from years past: 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2010.)

WHAT MISS MITCHELL SAW

“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles,” Maria Mitchell (August 1, 1818–June 28, 1889) often told her Vassar students — the world’s first university class of professionally trained women astronomers — having herself become America’s first professional woman astronomer, thanks to her historic discovery of a new telescopic comet on October 1, 1847, after sixteen tenacious years of sweeping the sky night after night.

“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles,” Maria Mitchell (August 1, 1818–June 28, 1889) often told her Vassar students — the world’s first university class of professionally trained women astronomers — having herself become America’s first professional woman astronomer, thanks to her historic discovery of a new telescopic comet on October 1, 1847, after sixteen tenacious years of sweeping the sky night after night.

Mitchell (whose extraordinary life was the seed for what became Figuring and to whom the inaugural Universe in Verse was dedicated) not only went on to blaze the way for women in STEM but used her prominence — she was arguably America’s first true scientific celebrity, welcomed in England, Italy, and Russia as a dignitary of the New World — to become one of the nineteenth century’s most ardent advocates for social reform, advancing women’s rights and abolition.

The epoch-making discovery that became the platform for Mitchell’s modeling of possibility and far-reaching influence is the kernel of the lovely picture-book What Miss Mitchell Saw (public library) by author Hayley Barrett and illustrator Diana Sudyka — a splendid addition to the most inspiring picture-book biographies of cultural heroes.

Barrett’s lyrical prose opens with a clever and tender solution to the common pronunciation confusion — Mitchell’s first name is spelled like my own but pronounced the presently atypical traditional Latin way:

On the first day of August, in a house tucked away on the fog-wrapped island of Nantucket, a baby girl was born.

Like all babies, this baby was given a name.

Her parents whispered it to her like a gentle breeze, ma…RYE…ah…

Names become a central creative trope in the book — the dignifying, truth-affirming act of calling all realities by their true names. We see the young Maria learn to recognize the ships of this whaling community by name and come to know the local shopkeepers by name.

Finally, after her father apprentices her as his astronomical assistant, she learns the stars by name — a testament to bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s astute observation that “finding the words is another step in learning to see.”

Sudyka’s beautiful gouache-and-watercolor illustrations weave together hand-lettered words from the story with the three great animating forces of Mitchell’s early life: the enchantment of the cosmos, the whaling culture of Nantucket, and her family’s Quaker values. (In Figuring, writing about the factors that fomented Mitchell’s unexampled ascent above the common plane of possibility for women in her era, I point to the original use of the word genius in the term genius loci — Latin for “the spirit of a place” — and wonder whether, despite her incontrovertible natural gift for mathematics, she would have so soared had she not grown up in a secluded whaling community, where matriarchs ruled while men spent months and years on whaling trips, where Quakers lived by the then-countercultural ethos of equal education for boys and girls, where a barren landscape and long winter nights turned astronomy into cherished popular entertainment.)

The book ends with the motto emblazoned on the gold medal Mitchell received from the King of Denmark for her landmark discovery — “Not in vain do we watch the setting and the rising of the stars” — a sentiment that echoes the dying words of the great astronomer Tycho Brahe, which Adrienne Rich incorporated into her exquisite tribute to Caroline Herschel, the world’s first professional woman astronomer: “Let me not seem to have lived in vain.”

See more of it here.

LAYLA’S HAPPINESS

“What is your idea of perfect happiness?” asks the famous Proust Questionnaire. Posed to David Bowie, he answered simply: “Reading.” Jane Goodall answered: “Sitting by myself in the forest in Gombe National Park watching one of the chimpanzee mothers with her family.” Proust himself answered: “To live in contact with those I love, with the beauties of nature, with a quantity of books and music, and to have, within easy distance, a French theater.”

“What is your idea of perfect happiness?” asks the famous Proust Questionnaire. Posed to David Bowie, he answered simply: “Reading.” Jane Goodall answered: “Sitting by myself in the forest in Gombe National Park watching one of the chimpanzee mothers with her family.” Proust himself answered: “To live in contact with those I love, with the beauties of nature, with a quantity of books and music, and to have, within easy distance, a French theater.”

The touching specificity of these answers and the subtle universality pulsing beneath them reveal the most elemental truth about happiness: that there are as many flavors of it as there are consciousnesses capable of registering it, and that it is a universally delicious necessity of life, which we crave from the day we are born until the day we die. And yet, as Albert Camus lamented, “happiness has become an eccentric activity. The proof is that we tend to hide from others when we practice it.”

Half a century later, as we wade through a world that gives us ample reason for sorrow, as existential credibility seems meted out on the basis of how loudly one broadcasts one’s disadvantage, the savoring of happiness has become an almost countercultural activity — an act of courage and resistance, and one the practice of which is a whole life’s work, as George Eliot well knew when she observed that “one has to spend so many years in learning how to be happy.” Why, then, not make the learning of happiness as essential a part of young people’s education as the learning of arithmetic? Or even stand with Elizabeth Barrett Browning in deeming it our moral obligation?

All of that — the personal nature of happiness, the daily practice of it, its centrality to participating meaningfully in the world — is what poet Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie explores in her vibrant and vitalizing picture-book debut, Layla’s Happiness (public library), illustrated by artist Ashleigh Corrin.

Like Sylvia Plath, who composed The Bed Book for her own children, Tallie — who describes herself in A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader as “the mother of three galaxies who look like daughters” — has written the book for her youngest galaxy, the book she wished she’d had to read to the elder two.

Tallie constructs the story like a good poem, where the personal is the most welcoming gateway to the universal. We see seven-year-old Layla — whose name means “night beauty” — tally her exuberant everyday sources of happiness.

Happiness leaps at Layla from the color purple, from the succulence of fresh plums, from the constellations of the night sky, from the mischievous delight of slurping spaghetti without a fork. It unspools from her lips as she hums while feeding the chickens at the community garden and names all the trees and greets the neighbors at the farmers’ market where she sells the vegetable she has grown from seeds. It pours forth from the poetry her mother reads to her under a makeshift tent and from the tales her father tells her of his own childhood in the South.

There is a heartening countercultural undertone to the book — these happinesses are not things to be purchased at the store or attained with a click, but embodiments of what Hermann Hesse held up as “the little joys” at the heart of a rich life lived with presence, the simple delights Wendell Berry’s childhood friend Nick savored even amid his hardship.

The book ends with an open question to the reader — a gentle bow to the sundry, deeply personal meaning of happiness.

See more of it here.

CINDERELLA LIBERATOR

“The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge,” Bertrand Russell wrote in his 1925 treatise on the nature of happiness shortly after Freud asserted that love and work are the bedrock of our mental health and our very humanity. In the century since, this notion has been taken to a warped extreme — love has been industrialized into the one-note Hollywood model of romance and work has metastasized into aching workaholism. Russell, one of the deepest and most nuanced thinkers our civilization has produced, was closer to the subtler truth, which we as a culture are still struggling to enact: that, while love and work are central to the good life, romantic love is not the only or even necessarily the most rewarding pinnacle of love; that a sense of curiosity and purpose, rather than the mechanistic drive for reward in exchange of effort, is the richest animating force of work; and that these two faces of life-satisfaction must face each other. Just as work alone is not enough for a fulfilling life, love alone is not enough for a fulfilling relationship, romantic or otherwise. No partnership of equals — that is, no truly satisfying partnership — can be complete without each partner recognizing and respecting in the other a sense of purpose beyond the relationship, a contribution to the world that reflects and advances that person’s deepest values and most impassioned dreams, in turn adding creative, intellectual, and spiritual fuel to the shared fire of the relationship.

“The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge,” Bertrand Russell wrote in his 1925 treatise on the nature of happiness shortly after Freud asserted that love and work are the bedrock of our mental health and our very humanity. In the century since, this notion has been taken to a warped extreme — love has been industrialized into the one-note Hollywood model of romance and work has metastasized into aching workaholism. Russell, one of the deepest and most nuanced thinkers our civilization has produced, was closer to the subtler truth, which we as a culture are still struggling to enact: that, while love and work are central to the good life, romantic love is not the only or even necessarily the most rewarding pinnacle of love; that a sense of curiosity and purpose, rather than the mechanistic drive for reward in exchange of effort, is the richest animating force of work; and that these two faces of life-satisfaction must face each other. Just as work alone is not enough for a fulfilling life, love alone is not enough for a fulfilling relationship, romantic or otherwise. No partnership of equals — that is, no truly satisfying partnership — can be complete without each partner recognizing and respecting in the other a sense of purpose beyond the relationship, a contribution to the world that reflects and advances that person’s deepest values and most impassioned dreams, in turn adding creative, intellectual, and spiritual fuel to the shared fire of the relationship.

We may know this intuitively, and we may have even demonstrated it empirically — that is just what Harvard’s landmark 75-year study of what makes a good life indicated — yet we remain trapped in the millennia-old cultural mythologies that have permeated even our most enlightened and progressive belief systems so deeply and so invisibly that their precepts remain largely unquestioned.

Rebecca Solnit offers a mighty antidote to those limiting precepts in Cinderella Liberator (public library) — an empowered and empowering retelling of the ancient story, which dates back at least two millennia and has recurred in various guises across nearly every culture since, reflecting and perpetuating our most abiding cultural myths about love, work, gender, success, waste and want, the measure of prosperity, and the meaning of purpose.

Governed by her conviction that “key to the work of changing the world is changing the story” and by her lifelong love of books as “toolkits you take up to fix things, from the most practical to the most mysterious, from your house to your heart,” Solnit retells the classic story, illustrated with century-old silhouettes by the great Arthur Rackham from a 1919 edition of the tale, in a way that liberates each character from the constrictions imposed upon him or her by someone else’s story and confers upon each the dignity of a complete human being with agency and autonomous dreams. Emerging from these simply worded, profound, richly rewarding pages is Solnit the literary artist, Solnit the revolutionary, Solnit the enchanter, Solnit the subtle and endlessly delightful satirist, Solnit the sage.

In one of the loveliest passages in the book, she wrests from the sad small lives of the two stepsisters, Pearlita and Paloma — who are later redeemed as mere victims of a cultural hegemony, and liberated — insight into and liberation from some of our most limiting beliefs. In consonance with Frida Kahlo’s touching testament to how love amplifies beauty and with my own conviction that there are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives, Solnit writes of the stepsisters’ preparations for the great ball:

Pearlita was doing her best to pile her hair as high as hair could go. She said that, surely, having the tallest hair in the world would make you the most beautiful woman, and being the most beautiful would make you the happiest.

Paloma was sewing extra bows onto her dress, because she thought that, surely, having the fanciest dress in the world would make you the most beautiful woman in the world, and being the most beautiful would make you the happiest. They weren’t very happy, because they were worried that someone might have higher hair or more bows than they did. Which, probably, someone did. Usually someone does.

But there isn’t actually a most beautiful person in the world, because there are so many kinds of beauty. Some people love roundness and softness, and other people love sharp edges and strong muscles. Some people like thick hair like a lion’s mane, and other people like thin hair that pours down like an inky waterfall, and some people love someone so much they forget what they look like. Some people think the night sky full of stars at midnight is the most beautiful thing imaginable, some people think it’s a forest in snow, and some people… Well, there are a lot of people with a lot of ideas about beauty. And love. When you love someone a lot, they just look like love.

There is love, then there is work: Along the way, we meet persons of various animations and occupations, unhinged from gender — the town blacksmith and the painter are each a “she,” the bird-doctor is a “he,” the dancing teacher is a “they,” and all are content making their particular contribution to the world. We learn that Cinderella is living with her evil stepmother because her own mother is a sea captain lost at sea. We see Cinderella and Prince Nevermind become friends rather than romantic partners, magnetized by a sincere curiosity about each other’s dreams rather than a possessive demand for romantic bondage. We find out that the prince would rather labor in an orchard than idle in a castle and Cinderella would rather open a farm-to-table cake shop that feeds refugee children from warring kingdoms than be court lady whose sole value is as a prince’s spouse and who has ceased to work because there are servants to do everything.

On the other side of the enchantment, the lizards-turned-footwomen and the mice-turned-horses and the rat-turned-coachwoman are each asked whether they actually want to remain footwomen and horses and a coachwoman for perpetuity — some do and some don’t, being individuals who dream different dreams and have different notions of self-actualization.

Solnit wrote the book for her beloved great-niece Ella, to whom her classic Men Explain Things to Me is also dedicated and whose name, Solnit realized with a shock only in the course of writing the story, is Cinderella liberated of the cinders. In the afterword to the book, on the cover of which Rackham’s cake-holding Cinderella resembles The Statue of Liberty and her torch, Solnit considers how these century-old silhouettes resonated with her broader motivations for the retelling:

I was also touched by Rackham’s image of the ragged child at work and thought of unaccompanied minors from Central America and immigrant domestic workers, who are a strong presence where I live, of foster children, and of all the children who live without kindness and security in their everyday lives, all the people who are outsiders even at home, or for whom home is the most dangerous place, or who have no home.

I liked the spirit of the silhouette-girl that Rackham portrayed. Even in rags she is lively, and she labors with alacrity, and runs and frolics wholeheartedly. She is stranded but not defeated. When it came time to write her story for our time, it seemed to me that the solution to overwork and degrading work is not the leisure of the princess, passing off the work to others, but good, meaningful work with dignity and self-determination — and one of the things the cake shop gives Cinderella, aside from independence, is the power to benefit others, because it’s also a meeting place.

Solnit reflects on the more personal roots of her story, inspired also by her two grandmothers, “both of whom were motherless girls, neglected, undereducated; neither of whom quite escaped that formative immersion in being unloved and unvalued.” She writes of one of them, a real-life Cinderella of the most tragic kind:

My paternal grandmother, Ida, was an unaccompanied refugee child who, after years without parents, made it from the Russian-Polish borderlands to Los Angeles with her younger brothers when she was fifteen. There, her long-lost father and stepmother also treated her as a servant.

Their tragedies were a century ago and more, but this book is also with love and hope for liberation for every child who’s overworked and undervalued, every kid who feels alone — with hope that they get to write their own story, and make it come out with love and liberation.

See more of it here.

THE FATE OF FAUSTO

In his short and lovely poem penned at the end of his life, Kurt Vonnegut located the wellspring of happiness in a source so simple yet so countercultural in capitalist society: “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

In his short and lovely poem penned at the end of his life, Kurt Vonnegut located the wellspring of happiness in a source so simple yet so countercultural in capitalist society: “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

A generation later, artist and author Oliver Jeffers — one of the most beloved and thoughtful storytellers of our time — picks up the message with uncommon simplicity of expression and profundity of sentiment in The Fate of Fausto (public library) — a “painted fable,” in that classic sense of moral admonition conveyed on the wings of enchantment, about how very little we and all of our striving matter in the grand scheme of time and being, and therefore how very much it matters to live with kindness, with generosity, in openhearted consanguinity with everything else that shares our cosmic blink of existence.

Inspired by Vonnegut’s poem, which appears on the final page of the book, the story follows a greedy suited man named Fausto, who decides he wants to own the whole world — from the littlest flower to the vastest ocean.

Building on Jeffers’s earlier illustrated meditation on the absurdity of ownership, the story is evocative of The Little Prince (which I continue to consider one of the greatest works of philosophy) and its archetypal characters, through whom Saint-Exupéry conveys his soulful existential admonition — the king who tries to make the Sun his subject; the businessman who, blind to the beauty of the stars, is busy tallying them in order to own them.

Perhaps Jeffers is paying deliberate homage to the beloved classic — the first two objects of Fausto’s hunger for ownership are a flower and a sheep.

One by one, he demands the surrender of sovereignty from all that he comes upon. The flower, being delicate and choiceless, assents to being owned by Fausto. The sheep, being sheepish, puts up no objection. Threatened, the tree bows down before him. (Oh how William Blake would have winced.)

When the lake questions Fausto’s self-appointed authority, he throws a tantrum to show the lake “who’s boss,” and the lake surrenders.

But when the mountain, grounded in her autonomy, refuses to move, Fausto flies into a fit of fury so menacing that even the mountain breaks down and submits to being owned.

Restless with not-enoughness, not content to own the flower and the sheep and the tree and the lake and the mountain, Fausto usurps a boat and heads for the open sea.

Alone amid the blue expanse, he bellows his claim of ownership. But the sea is silent. Fausto yells louder still, unsure quite where to aim his fury, for the sea stretches in all directions.

Finally, the sea responds, calmly questioning how Fausto can wish to own her if he doesn’t even love her. Oh but he does, he does, the riled Fausto insists. The sea, in consonance with the great humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm’s observation that “understanding and loving are inseparable,” tells Fausto that he couldn’t possibly love her if he doesn’t understand her.

Anxious to stake his claim, Fausto scolds the sea for being wrong, barks that he understands her deeply, then swiftly demands that she submit to his ownership or he will show her who’s boss.

“And how will you do that?” asks the sea. By making a fist and stamping his foot, Fausto replies. With her primordial wisdom, having witnessed human folly since the dawn of humanity, the sea invites Fausto to show her just how he plans to stamp his foot, so she can understand. And Fausto, “in order to show his anger and omnipotence,” perches overboard and aims his foot at the sea.

Swiftly, inevitably, the laws of physics and human hubris take hold of Fausto, who disappears into the fathomless sea — a sinking testament to Ursula K. Le Guin’s cautionary charge that unbridled anger “feeds off itself, destroying its host in the process.” (How fitting, too, that Jeffers should choose the world of water — one of his supreme fixations as an artist, subject of some of his most haunting conceptual paintings — as the arena on which this final existential battle between the human animal and its ego plays out.)

Jeffers’s subtle, powerful message emerges with the tidal force of elemental truth: When all is said and done and sunk and swallowed, there is only the realization at which Dostoyevsky arrived in his stark brush with death: that “life is a gift, life is happiness, each moment could have been an eternity of happiness,” had it been lived with a sympathetic love of the world.

The sea, Jeffers tells us, feels sorry for Fausto, but goes on being a sea, as the mountain does being a mountain.

And the lake and the forest,

the field and the tree,

the sheep and the flower,

carried on as before.For the fate of Fausto

did not matter to them.

We are dropped safely ashore to contemplate the fundamental fact that our lives — along with all of our yearnings and fears, our most small-spirited grudges and most largehearted loves, our greatest achievements and deepest losses — will pass like the lives and loves and losses of everyone who has come before us and everyone who will come after. Temporary constellations of matter in an impartial universe of constant flux, we will come and go as living-dying testaments to Rachel Carson’s lyrical observation that “against this cosmic background the lifespan of a particular plant or animal appears, not as drama complete in itself, but only as a brief interlude in a panorama of endless change.” The measure of our lives — the worthiness or worthlessness of them — resides in the quality of being with which we inhabit the interlude.

See more of it here.

OVER THE ROOFTOPS, UNDER THE MOON

“You can be lonely anywhere, but there is a particular flavour to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people,” Olivia Laing wrote in her lyrical exploration of loneliness and the search for belonging. Our need for belonging is indeed the warp thread of our humanity, and our locus of belonging — determined in part by our choices and in part by the cards chance has dealt us in what we were born as and where — is a pillar of our identity. For those who have migrated far from their homeland, and especially for those of us who have migrated alone, without the built-in social support structure of a community or a family unit, this rupture of belonging can be particularly disorienting and lonesome-making. “You only are free when you realize you belong no place — you belong every place,” Maya Angelou told Bill Moyers in their fantastic 1973 conversation about freedom — a freedom the conquest of which can be a whole life’s work.

“You can be lonely anywhere, but there is a particular flavour to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people,” Olivia Laing wrote in her lyrical exploration of loneliness and the search for belonging. Our need for belonging is indeed the warp thread of our humanity, and our locus of belonging — determined in part by our choices and in part by the cards chance has dealt us in what we were born as and where — is a pillar of our identity. For those who have migrated far from their homeland, and especially for those of us who have migrated alone, without the built-in social support structure of a community or a family unit, this rupture of belonging can be particularly disorienting and lonesome-making. “You only are free when you realize you belong no place — you belong every place,” Maya Angelou told Bill Moyers in their fantastic 1973 conversation about freedom — a freedom the conquest of which can be a whole life’s work.

Poet JonArno Lawson, author of the wondrous Sidewalk Flowers, and artist Nahid Kazemi take up these complex questions with great simplicity and thoughtful sensitivity in Over the Rooftops, Under the Moon (public library) — a spare, poetic meditation on belonging and what it means to be oneself as both counterpoint and counterpart to otherness, as a thinking, feeling, wakeful atom of life amid the constellation of other atoms.

We meet a melancholy young bird, lonesome even among the other birds, lonesome while soaring above the cityscape, above houses filled with innumerable lives that feel so impossibly distant and alien.

Lawson writes:

You can be far away inside,

and far away outside.

One day, something subtle but profound shifts in the bird — the gaze of a young girl sparks a quickening of heart, a certain opening to the possibility of belonging, a new curiosity about the nature of life — about what it means to be.

We see the bird’s plumage suddenly explode with color — the radiance of awakening, evocative of poet Jane Kenyon’s piercing line: “What hurt me so terribly all my life until this moment?”

Color arrives,

sometimes when

you least expect it.

The story unfolds with a poet’s precision and economy of words, punctuated by Kazemi’s sprawling, stunning watercolors. What emerges is a gentle invitation to what Bertrand Russell so beautifully termed “a largeness of contemplation.”

The bird moves through seasons of change, floats wordlessly across landscapes of possibility, alighting at last to a vastly different world — more colorful, more alive. In this foreign-looking land, which Kazemi’s palm trees and Middle Eastern architecture contrast with the deciduous crowns and Western cityscapes of the melancholy world, the bird finds a homecoming among other birds — a newfound joy in being “alone and together, over the rooftops and under the moon.”

See more of it here.

MY HEART

“How is your heart?” I recently asked a friend going through a trying period of overwork and romantic tumult, circling the event horizon of burnout while trying to bring a colossal labor of love to life. His answer, beautiful and heartbreaking, came swiftly, unreservedly, the way words leave children’s lips simple, sincere, and poetic, before adulthood has learned to complicate them out of the poetry and the sincerity with considerations of reason and self-consciousness: “My heart is too busy to be a heart,” he replied.

“How is your heart?” I recently asked a friend going through a trying period of overwork and romantic tumult, circling the event horizon of burnout while trying to bring a colossal labor of love to life. His answer, beautiful and heartbreaking, came swiftly, unreservedly, the way words leave children’s lips simple, sincere, and poetic, before adulthood has learned to complicate them out of the poetry and the sincerity with considerations of reason and self-consciousness: “My heart is too busy to be a heart,” he replied.

How does the human heart — that ancient beast, whose roars and purrs have inspired sonnets and ballads and wars, defied myriad labels too small to hold its pulses, and laid lovers and empires at its altar — unbusy itself from self-consciousness and learn to be a heart? That is what artist and illustrator Corinna Luyken explores in the lyrical and lovely My Heart (public library) — an emotional intelligence primer in the form of an uncommonly tender illustrated poem about the tessellated capacities of the heart, about love as a practice rather than a state, about how it can frustrate us, brighten us, frighten us, and ultimately expand us.

My heart is a window,

My heart is a slide.

My heart can be closed

or opened up wide.Some days it’s a puddle.

Some days it’s a stain.

Some days it is cloudy

and heavy with rain.

Across the splendid spare verses, against the deliberate creative limitation of a greyscale-and-yellow color palette, a sweeping richness of emotional hues unfolds. What emerges is one of those rare, miraculous “children’s” books, in the tradition of The Little Prince, teaching kids about some elemental aspect of being human while inviting grownups to unlearn what we have learned in order to rediscover and reinhabit the purest, most innocent truths of our humanity.

Some days it is tiny,

but tiny can grow…

and grow…

and grow.

There are days it’s a fence

between me and the world,

days it’s a whisper

that can barely be heard.There are days it is broken,

but broken can mend,

and a heart that is closed

can still open again.

My heart is a shadow,

a light and a guide.

Closed or open…

I get to decide.

See more of it here.

CRESCENDO

“Every man or woman who is sane, every man or woman who has the feeling of being a person in the world, and for whom the world means something, every happy person, is in infinite debt to a woman,” the trailblazing psychologist Donald Winnicott observed in his landmark manifesto for the mother’s contribution to society. Inseparable from the psychological role of mothering is the biological reality of motherhood — a biology almost alien in its otherworldly strangeness as a cell becomes a being, with a heart and a mind and a whole life ahead.

“Every man or woman who is sane, every man or woman who has the feeling of being a person in the world, and for whom the world means something, every happy person, is in infinite debt to a woman,” the trailblazing psychologist Donald Winnicott observed in his landmark manifesto for the mother’s contribution to society. Inseparable from the psychological role of mothering is the biological reality of motherhood — a biology almost alien in its otherworldly strangeness as a cell becomes a being, with a heart and a mind and a whole life ahead.

That glorious strangeness is what Paola Quintavalle celebrates in Crescendo (public library) — an uncommon picture-poem about the science of pregnancy, evocative of Ursula K. Le Guin’s lovely insistence that “science describes accurately from outside, poetry describes accurately from inside [and] both celebrate what they describe.”

Unfolding across lyrical watercolors by Italian artist Alessandro Sanna — who painted the wordless masterpieces Pinocchio: The Origin Story and The River — the story follows the growth of an almost-being inside a mother’s womb over the nine months of gestation. As small as a sesame seed, it soon sprouts the buds that will blossom into arms and legs, grows its first organ — the heart — and develops its first senses, smell and sound.

By the third month, the fetus gets its fur coat, known as lanugo, and the first fragments of its miniature skeleton begin to form. By month four, fingerprints are being carved onto its tiny digits.

Visual metaphors drawing on the lives of other beings — a bird, a horse, a flower, a school of fish — populate Sanna’s watercolor score of Quintavalle’s spare, poetic chronicle of becoming, their geometry cleverly mirroring the curvature of the mother’s belly that frames the story.

What strikes me is that each of us has undergone this absolutely astonishing process, with no conscious memory of it at all, and yet somehow we don’t walk around in perpetual astonishment that this is how we came to be. Perhaps we should. I am reminded of the great poet and philosopher of science Loren Eiseley’s words: “We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness. We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.”

See more of it here.

THE SHORTEST DAY

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” Annie Dillard wrote in her timely exhortation for presence over productivity. It may be an elemental feature of our condition that the more scarce something is, the more precious it becomes. Just as the shortness of life calls, in that Seneca way, for filling each year with breadths of experience, so the shortness of the day calls for the fulness of each hour, each moment. No day concentrates and consecrates its elementary particles of time more powerfully than the shortest day of the year. With our awareness pointed to its brevity by ancient rites and modern calendars alike, as we “rage, rage against the dying of the light,” something rapturous happens — a kind of portal into heightened presence opens up as every minute ticks with a supra-consciousness of its passage, pulsates with an extra fulness of being, while at the same time attuning us to the cyclical seasonality of time, reminding us of the cycles of life and death.

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” Annie Dillard wrote in her timely exhortation for presence over productivity. It may be an elemental feature of our condition that the more scarce something is, the more precious it becomes. Just as the shortness of life calls, in that Seneca way, for filling each year with breadths of experience, so the shortness of the day calls for the fulness of each hour, each moment. No day concentrates and consecrates its elementary particles of time more powerfully than the shortest day of the year. With our awareness pointed to its brevity by ancient rites and modern calendars alike, as we “rage, rage against the dying of the light,” something rapturous happens — a kind of portal into heightened presence opens up as every minute ticks with a supra-consciousness of its passage, pulsates with an extra fulness of being, while at the same time attuning us to the cyclical seasonality of time, reminding us of the cycles of life and death.

That is what writer Susan Cooper and artist Carson Ellis celebrate in The Shortest Day (public library) — an illustrated resurrection of Cooper’s 1974 poem by the same title, originally composed for John Langstaff’s beloved Christmas Revel shows, which fuse medieval and modern music in grassroots theatrical productions across local communities.

Cooper’s buoyant verses and Ellis’s soulful, mirthful illustrations bring to life, across time and space and cultures and civilizations, the ardor with which our ancestors have welcomed the winter solstice since long before the astronomer Johannes Kepler coined the word orbit in an era when few dared believe that the Earth spins on its axis while revolving around the Sun. (It is a function of the tilt of Earth’s axis and the elliptical shape of its orbit — another radical contribution of Kepler’s, who debunked the millennia-old dogma of perfect circular motion — that when our planet’s axial tilt leans one pole as far away as it would go from our star, we are granted the shortest possible day and the longest possible night of the year.)

So the shortest day came, and the year died,

And everywhere down the centuries of the snow-white world

Came people singing, dancing,

To drive the dark away.

See more of it here.

WHAT IF…

“The present is not a potential past; it is the moment of choice and action,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote. At bottom, choice and action always begin with “what if” — the mightiest spring for the utopian imagination, the fulcrum by which every revolution rolls into being. What if this world were freer, more beautiful, more just? “We will not know our own injustice if we cannot imagine justice. We will not be free if we do not imagine freedom,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in weighing the transformative power of the speculative imagination. “We cannot demand that anyone try to attain justice and freedom who has not had a chance to imagine them as attainable.”

“The present is not a potential past; it is the moment of choice and action,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote. At bottom, choice and action always begin with “what if” — the mightiest spring for the utopian imagination, the fulcrum by which every revolution rolls into being. What if this world were freer, more beautiful, more just? “We will not know our own injustice if we cannot imagine justice. We will not be free if we do not imagine freedom,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in weighing the transformative power of the speculative imagination. “We cannot demand that anyone try to attain justice and freedom who has not had a chance to imagine them as attainable.”

That chance to imagine a better world is what French author Thierry Lenain and artist Olivier Tallec invite in What If… (public library), translated by Enchanted Lion founder Claudia Bedrick — a lovely celebration of our civilizational responsibility, in the beautiful words of the cellist Pablo Casals, “to make this world worthy of its children” and a testament to James Baldwin’s sobering insistence that “we made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over.”

Although we don’t yet know it, the story begins with an unborn child imagining himself into being as he imagines a better version of the world to be born into. Where he sees war, he imagines turning the soldiers’ guns into bird perches and shepherd’s flutes. Where he sees drought and famine, he imagines pulling rainclouds over the desert like enormous kites.

He places his child-body between the “gorging, ordering, shouting, and decreeing” orange-haired politician on the TV screen and the people mesmerized before it. He sits on the ocean shore and imagines it clean of human-inflicted pollution, buoying colorful fish.

He falls asleep on a mossy patch in the forest, listening to the wisdom of the trees. He sees heartache and tears, and imagines them salved by love.

“We have to hug,” he decided, “and not be afraid of kisses. What if we start saying ‘I love you,’ even if we’ve never heard it before?”

See more of it here.

LISTEN

“To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote as she contemplated the art of seeing. To listen takes time, too — to learn to hear and befriend the world within and the world without, to attend to the quiet voice of life and heart alike. “If we were not so single-minded about keeping our lives moving, and for once could do nothing,” Pablo Neruda wrote in his gorgeous ode to quietude, “perhaps a huge silence might interrupt this sadness of never understanding ourselves.”

“To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote as she contemplated the art of seeing. To listen takes time, too — to learn to hear and befriend the world within and the world without, to attend to the quiet voice of life and heart alike. “If we were not so single-minded about keeping our lives moving, and for once could do nothing,” Pablo Neruda wrote in his gorgeous ode to quietude, “perhaps a huge silence might interrupt this sadness of never understanding ourselves.”

This inspiriting, sanctifying power of listening is what writer Holly M. McGhee and illustrator Pascal Lemaître explore in the simply titled, sweetly unfolding Listen (public library) — a serenade to the heart-expanding, life-enriching, world-ennobling art of attentiveness as a wellspring of self-understanding, of empathy for others, of reverence for the loveliness of life, evocative of philosopher Simone Weil’s memorable assertion that “attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer.”

Lemaître — who has previously illustrated the children’s book about kindness Toni Morrison co-wrote with her own son — brings McGhee’s buoyant words to life in his spare, infinitely tender lines and gentle washes of color.

Listen

to the sound of your feet —

the sound of all of us

and the sound of me.

The stars —

they are for you

and all of us.

They are for me.

The simple verses beckon the attention to envelop the whole world, from the immediacy of one’s own sensorial surroundings — the ground, the Sun, the air, the stars — to the widening awareness of our shared belonging and our intertwined fates. Radiating from them is Einstein’s notion of “widening circles of compassion” and Dr. King’s immortal insistence that “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.”

Breathe.

Smell the air.

My air is yours and all of ours,

your air is mine.

Your heart can hold everything.

Including the world —

its darkness and its light.Including your story,

including my story —

including the story

of all of us…

See more of it here.

ROAR LIKE A DANDELION

“Her lovely and original poetry has a flexibility that allowed me the maximum of space to execute my fantasy variations on a Kraussian theme,” Maurice Sendak wrote of the great children’s book author and poet Ruth Krauss (July 25, 1901–July 10, 1993), with whom he collaborated on two of the loveliest, tenderest picture-books of all time.

“Her lovely and original poetry has a flexibility that allowed me the maximum of space to execute my fantasy variations on a Kraussian theme,” Maurice Sendak wrote of the great children’s book author and poet Ruth Krauss (July 25, 1901–July 10, 1993), with whom he collaborated on two of the loveliest, tenderest picture-books of all time.

A quarter century after the end of Krauss’s long life, lost fragments of her daring poetic imagination coalesced into a manuscript that alighted to the desk of one of the great picture-book artists of our own time: Sergio Ruzzier. The resulting collaboration, across lines of space and time and life and death, is the wondrously imaginative Roar Like a Dandelion (public library), the dedication of which, penned by Ruzzier in a spirit of creative kinship and reverence, reads simply: “To Maurice.”

Though structured as an ABC book, in a succession of short sentences each beginning with a consecutive letter of the alphabet, the book is rather an alphabetic catalogue of Krauss’s quirky, free-spirited, infinitely playfully, subtly profound prescriptions for joy and existential contentment.

“Vote for yourself,” Krauss urges under V, as a Ruzzier piglet is seen pledging allegiance to herself — that ultimate act of self-respect, the pillar of character.

“Roar like a dandelion,” she exhorts in the line that lent the book its title, which sits like a Zen koan, to be contemplated from a thousand directions before it can be cracked, suggesting maybe that the mightiest roar is the silent roar; maybe that anger is corrosive to its host, for if a dandelion were indeed to roar, it would blow up its own delicate seedhead and lose all of its fluffy white parachutes of hope; maybe that the dandelion’s yellow burst of blossom, so plentiful if we only pay attention, is nature’s primal scream of joy.

“Make music,” Krauss beckons in consonance with Sendak, who ardently believed that the making of music is the profoundest and most primitive expression of our intrinsic nature.

Page after page, letter by letter, Ruzzier’s sweet, and stubborn creatures leap and tumble along the lines of Krauss’s imagination with their joyous, mischievous magic.

See more of it here.

ALSO: A VELOCITY OF BEING

It feels a little strange to include A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader (public library) here, because it was originally published in the final days of 2018 and because, of course, it is my very own labor of love. But it would be as strange not to include it — not because I devoted eight years of my life to this charitable endeavor, but because the first edition vanished into eager hands within a day, leaving scores of sweetly disappointed readers to wave theirs with unslaked eagerness into the new year. Since most of the world didn’t meet the book until 2019, I too must consider it a baby of this year.

It feels a little strange to include A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader (public library) here, because it was originally published in the final days of 2018 and because, of course, it is my very own labor of love. But it would be as strange not to include it — not because I devoted eight years of my life to this charitable endeavor, but because the first edition vanished into eager hands within a day, leaving scores of sweetly disappointed readers to wave theirs with unslaked eagerness into the new year. Since most of the world didn’t meet the book until 2019, I too must consider it a baby of this year.

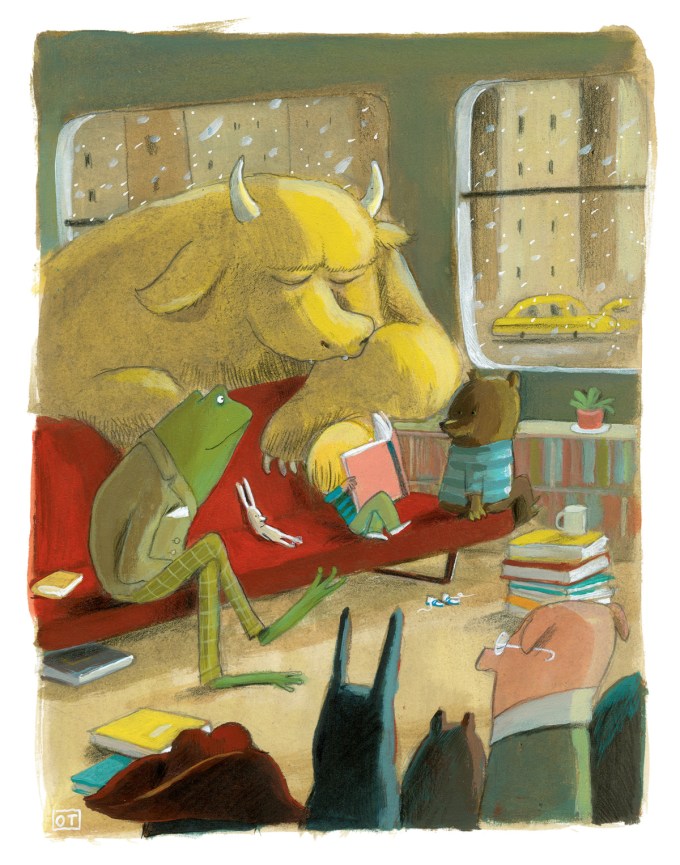

This collection of original letters to the children of today and tomorrow about why we read and what books do for the human spirit, all proceeds from which benefit the New York public library system, features contributions by 121 of the most interesting and inspiring humans in our world, including Jane Goodall, Yo-Yo Ma, Jacqueline Woodson, Ursula K. Le Guin, Mary Oliver, Neil Gaiman, Amanda Palmer, Rebecca Solnit, Elizabeth Gilbert, Shonda Rhimes, Alain de Botton, James Gleick, Anne Lamott, Diane Ackerman, Judy Blume, Eve Ensler, David Byrne, Sylvia Earle, Richard Branson, Marina Abramović, Regina Spektor, Elizabeth Alexander, Adam Gopnik, Debbie Millman, Tim Ferriss, a 98-year-old Holocaust survivor, Italy’s first woman in space, and many more immensely accomplished and largehearted artists, writers, scientists, philosophers, entrepreneurs, musicians, and adventurers whose character has been shaped by a life of reading.

Accompanying each letter is an original illustration by a prominent artist in response to the text — including beloved children’s book illustrators like Sophie Blackall, Oliver Jeffers, Isabelle Arsenault, Jon Klassen, Shaun Tan, Olivier Tallec, Christian Robinson, Marianne Dubuc, Lisa Brown, Carson Ellis, Mo Willems, Peter Brown, and Maira Kalman.

See more of the art here and read some of the loveliest letters here.

—

Published December 16, 2019

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2019/12/16/favorite-childrens-books-of-2019/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr